Ostriches are large flightless birds, of the genus Struthio, in the order Struthioniformes, part of the infra-class Palaeognathae, a diverse group of flightless birds also known as ratites that include the emus, rheas, and kiwis.

There are two living species of ostrich: the common ostrich, native to large areas of sub-Saharan Africa, and the Somali ostrich, native to the Horn of Africa. The common ostrich was also historically native to the Arabian Peninsula,

and ostriches were present across Asia as far east as Mongolia during the Late Pleistocene[1] and possibly into the Holocene[2]. The genus Struthio was first described by Carl Linnaeus[3] in 1758. The earliest fossils of the genus Struthio are from the early Miocene[4] ~21 million years ago in Namibia in Africa, so it is proposed that the genus is of African origin.

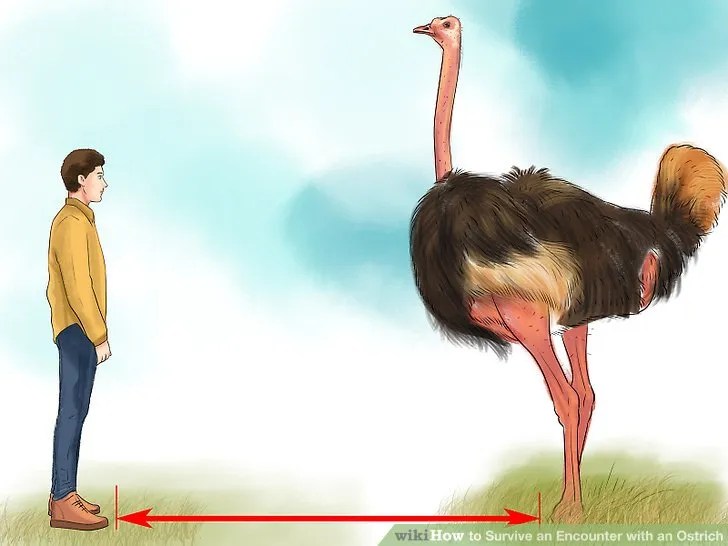

They grow 7 to 9 feet tall and weigh 220 to 350 pounds. Ostriches are omnivores and travel in herds. They roam African savanna and desert lands and get most of their water from the plants they eat.

Though they cannot fly, ostriches are fleet, strong runners. They can sprint up to 43 miles an hour and run over distances at 31 miles an hour. They may use their wings as “rudders” to help them change direction while running.

An ostrich’s powerful, long legs can cover 10 to 16 feet in a single stride. These legs can also be formidable weapons. Ostrich kicks can kill a human or a potential predator like a lion. Each two-toed foot has a long, sharp claw.

Lions, cheetahs, leopards, and hyenas hunt ostriches and prey on their eggs. An ostrich’s first line of defense is to run fast and far. If there are chicks to protect or fleeing isn’t an option, ostriches stop predators with a powerful kick. Sharp claws on their toes can deliver a damaging blow. An ostrich may also use its body as a ram to knock a predator to the ground.

Their herds usually contain less than a dozen birds. Alpha males maintain these herds and mate with the group’s dominant hen. The male sometimes mates with others in the group, and wandering males may mate with lesser hens. The group’s hens place their eggs in the dominant hen’s nest—though her own are given the prominent center place. The dominant hen and male take turns incubating the giant eggs, each weighing as much as two dozen chicken eggs. The incubation period of an ostrich egg is between 35 and 45 days, but despite this short period of time, less than 10% of nests survive this long.

Does an ostrich really bury its head in the sand?

No, this is a common misconception! Ostriches dig their nests in the ground and will sometimes poke their heads in to check on or move their eggs. Additionally, when ostriches sense danger approaching, they may lie down low and press their long necks to the ground to become less visible. Both of these behaviors have led to the myth that ostriches bury their heads in the sand.

One of an ostrich’s more famous characteristics, its long, thick eyelashes are actually an adaptation in response to risks associated with sandstorms. Because ostriches live in a semi-arid habitat, sand and dust storms are common and can cause damage to animals’ vision and, sometimes, respiratory systems. The ostrich’s eyelashes can help limit this damage.

Their diet consists mainly of roots, leaves, and seeds, but ostriches will eat whatever is available. Sometimes they consume insects, snakes, lizards, and rodents.

They also swallow sand and pebbles which help them grind up their food in their gizzard, a specialized, muscular stomach. Because ostriches have this ability to grind food, they can eat things that other animals cannot digest. Oftentimes groups of ostriches will graze among giraffes, zebras, gnus, and antelopes. Their presence is useful because they alert other animals when danger is near.

Why can’t an ostrich fly?

Ostriches are heavy with small flight wings and a flattened sternum (breastbone). The sternum in flying birds is keel-shaped (like the hull of a ship), and the powerful wing muscles are attached to it. A bird can’t be cleared for takeoff without that keel bone, so ostriches remain grounded.

Footnotes

- The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as Upper Pleistocene from a stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. It is currently defined as the time between c. 129,000 and c. 11,700 years ago. [Back]

- The Holocene Climate Optimum (HCO) was a warm period that occurred in the interval roughly 9,000 to 5,000 years ago BP, with a thermal maximum of around 8000 years BP. It has also been known by many other names, such as Altithermal, Climatic Optimum, Holocene Megathermal, Holocene Optimum, Holocene Thermal Maximum, Hypsithermal, and Mid-Holocene Warm Period. [Back]

- Carl Linnaeus (May 23, 1707 – January 10, 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné, was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalized binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming organisms. He is known as the “father of modern taxonomy”. [Back]

- The Miocene is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about 23.03 to 5.333 million years ago. The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words μείων (meíōn, “less”) and καινός (kainós, “new”) and means “less recent” because it has 18% fewer modern marine invertebrates than the Pliocene has. The Miocene is preceded by the Oligocene and is followed by the Pliocene. [Back]

Further Reading

Sources

One Kind Planet

Wikipedia

National Geographic

Treehugger

PBS

Smithsonian’s National Zoo & Conservation Biology Institute

Animal Fact Guide

Mental Floss

San Diego Zoo